This article will deal with issues of pregnancy loss and stillbirth, with photos of mummified human remains.

King Tut, short for Tutankhamun, is arguably one of the most recognized ancient Egyptian pharaohs despite his short life and shorter rule around 3300 years ago yet there is a lot of misconceptions about him in popular culture.

So let’s begin with a little background information about his life and learn more about the tiny coffins found in his tomb.

Meet the Family

King Tut’s grandfather, Amenhotep III, ruled Egypt during one of its most prosperous eras. While his father, Akhenaten, was a heretic who attempted to remake Egypt as a monotheistic realm. Akhenaten wanted to do away with all the gods of Egypt and worship just one supreme deity, the Sun god, Aten (as opposed to Amun Ra, who was the dual sun god in the traditional pantheon).

With the help of his advisor and military leader, Ay, Akhenaten moved the capital of Egypt from Thebes to Amarna. This even influenced the style of art, so named Amarna Style, which was still highly stylized (reminds me of art deco) but with more emotionally naturalistic themes. In the limestone basrelief above we see Akhenaten with his wife Nefertiti and their three daughters. The family sits in the rays of Aten, Akhenaten is cuddling and kissing one of his daughters, while his wife holds one on her lap and another climbs her side, pulling on an earring or crown accessory.

King Tut’s family was more of a bramble than a tree: His grandparents were not closely related however he only had the one set. His mother and father were full siblings, his mother was known as The Younger Lady but she wasn’t his father’s main wife. Akhenaten’s main wife was Nefertiti, and she was the mother of Ankesenamun. (We saw them in the basrelief.) Akhenaten had his children by these two wives, Ankesenamun and Tutankhamun, half-siblings, marry each other.

Tutankhamun’s Reign

When King Tutankhamun became pharaoh around age ten, his goal (or his advisors’ goal) was to return Egypt to the way it was before his father’s twenty-year rule, not just reinstate the traditional pantheon and move the capital back to Thebes– but provide the realm with the unprecedented wealth and peace of the earlier 18th dynasty. No pressure kid. Speaking of his youth, he only became pharaoh because he was the last male in his family line. His older brother, Smenkhare, ruled for less than a year before he died. So Tut’s job was to do all this and to have a lot of children, preferably male, asap.

During his time as pharaoh, from age nine to about nineteen, he took pains to distance himself as much as possible from the heretical actions of his father, including changing his name from Tutankh-aten to Tutankh-amun. While he managed to revert the kingdom to the old religion and moved the capital back to Thebes, he failed to produce an heir. At his death, King Tut left no living children and his widow Ankhesenamun married his (and their father’s) former advisor and successor, Ay.

If you have seen the contents of King Tut’s tomb you may think that it was an examplar of Pharonic tombs, however, Tutankhamun was laid to rest in a relatively simple tomb. Some have used this as evidence that he wasn’t powerful or well respected, going so far as to claim his humble tomb is evidence that he was murdered. Considering his wife’s subsequent marriage to Ay, which made him Pharaoh, point the finger at the advisor or the advisor and the wife for King Tut’s premature death– but there is no evidence that he was murdered.

But this simple tomb wasn’t necessarily a sign of disrespect but used because there was no time to create a royal tomb before the 70-day post-death internment requirement in their belief system– which belies the fact that King Tut was considered healthy and not expected to die any time soon. However small it was, the tomb was stuffed with thousands of precious items including gold, gems, and newly developed decorative glasswork.

Rediscovering King Tut

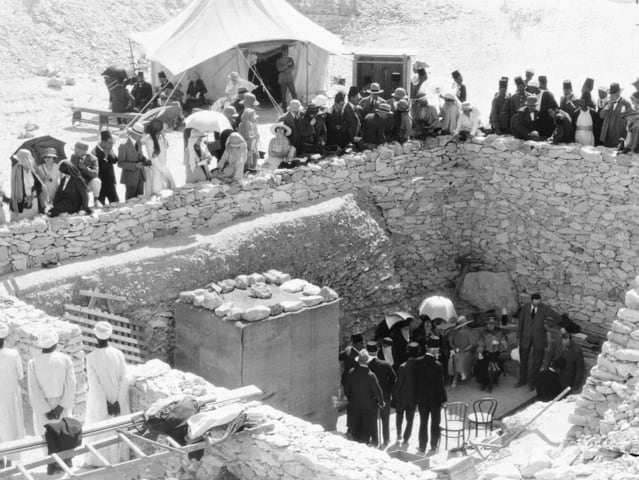

King Tut’s tomb was robbed twice, perhaps within months of his death and was restored following each breech, but ultimately living memory of the boy king and his final resting place was was lost (literally, under the building debris for other tombs) for thousands of years.

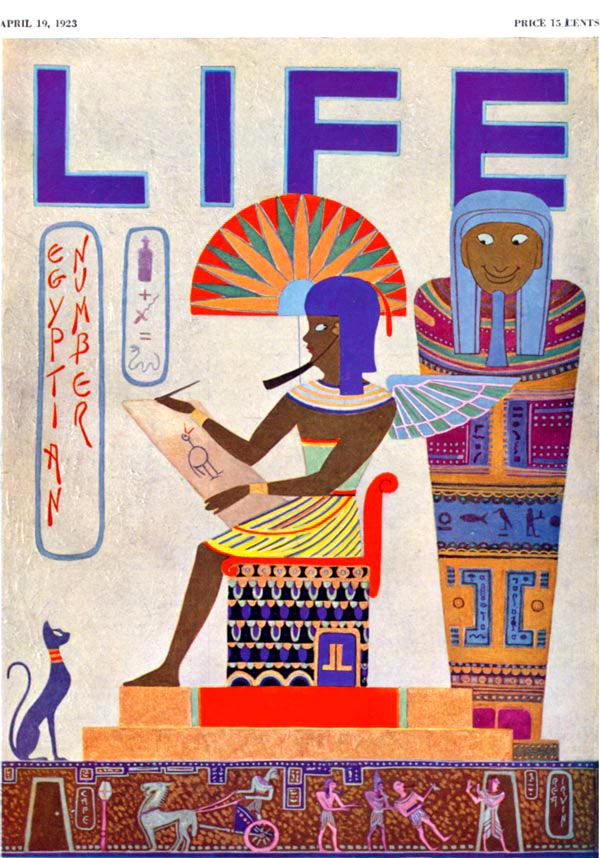

Just over one hundred years ago, Archeologist Howard Carter and his team rediscovered the tomb in 1922. The find caused a fad for all things Ancient Egyptian, the press called it “Egyptomania” and its rediscovery coupled with photography and film technology is the reason King Tut is so well known today. It took Carter’s team ten years to catalogue each of the 5,398 items.

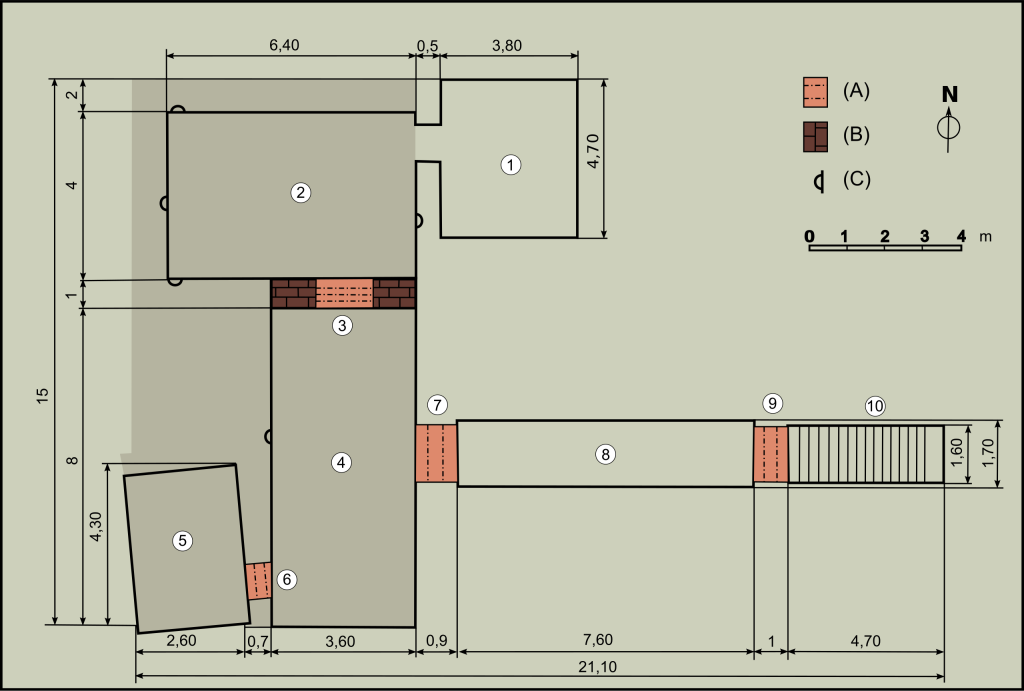

Item 317

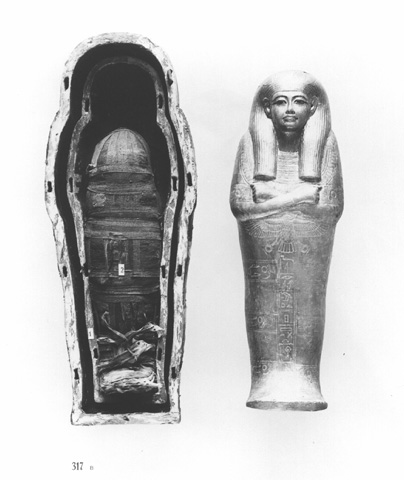

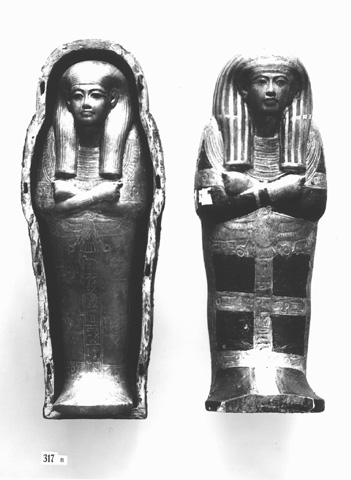

In 1925, they listed a box (item 317) containing two tiny nested coffins which were catalouged as items 317a and 317b. The outer coffins were coated in black resin and painted gold stripes and instead of personal names, they were both labeled with the name Orisis, the god of the dead. The inner coffins were gilded with bands joined with clay seal impressions of “the jackal and nine captives[…] or the nine enemies of Egypt” (Hawass et al). Which I don’t completely understand but I found it interesting– were these tiny mummies intended to protect the tomb or King Tut’s soul from the enemies of Egypt?

317a

In 1925, Carter had the smaller mummy unwrapped and photographed:

“Head covered with a gesso-gilt mask, several sizes too large.”

“The wrappings comprised about 1.5 cents in thickness, but were in bad order; pads over chest, legs & stiffeners for feet were very apparent.”

“A child of premature birth, perfectly preserved.”

Howard Carter’s Notes

Afterward, Carter catalouged them, both mummies were removed from their coffins, wrapped in thick cotton batting and set inside individual wooden boxes and sent to the Cario Medical University for further study.

In 1932, Douglas Derry performed autopsies on the tiny mummies: both were female, and of 317a he recorded:

“On the head are visible many fine whitish hairs of a silky appearance probably the remains of lanugo.”

“it is estimated from the length of the foetus, the absence of eyelashes and the state of the eyelids, that the intrauterine age of the child when born could not have exceeded five months.”

Douglas Derry’s Autopsy Notes 317a

317b

“There is no sign of the umbilical cord but the appearance of the navel which is not retracted suggests that the cord had been removed by cutting it off close to the abdominal wall and that it had not dried up as it would had the child lived.”

“the eyebrows and eyelashes were visible; the eyes were open, and there was downy hair on the scalp.”

Douglas Derry’s Notes

At that time both were described as perfectly preserved but throughout the 20th century and into the early 21st, they were stored in the wooden box and cotton batting that Carter’s team packed them into (after destroying their wrappings). Kept in an environmentally unregulated room at Cario Medical University, while their coffins were kept at the Grand Egyptian Museum. Today, 317a and 317b are in a poor state of preservation but are now being conserved.

But questions remained: who were these babies? did they have names? who were their parents? and why were they in King Tut’s tomb?

Medical Theories

Tutankhamun’s Health

In the 1970s, new medical theories about King Tut were being developed to explain his young age at death and lack of heirs. Most of these theories focused on the inbreeding in his family (sibling marriage of his parents) that they believed caused terrible medical problems for King Tut. Today there is no lack of sources claiming that King Tut was an inbred freak show who could barely walk or eat, with bad teeth, a twisted spine, manboobs, big hips, and a club foot.

It started with the sculptures found in his tomb, apparently of him in pharaonic headgear, but featuring breasts. Without any physical evidence (his chest area was missing from his mummy), it was assumed that Tutankhamun had gynecomastia (man boobs) and therefore had an adrenal tumour, or Klinefelter’s and/or Wilson’s syndromes and thus was infertile or even intersexed. Therefore the infants found in his tomb could not have been his biological children.

These theories were promoted despite records stating clearly that his penis, though since detached from his body, was well developed and possibly even erect when he was mummified (ftr, it doesn’t mean he was doing the deed when he died, a male body can develop priapism during or after death, a condition cleverly named “death erection”).

When it was pointed out that multiple 18th dynasty pharaohs (known to have fathered children) were depicted with manboobs and potbellies in art, the updated diagnosis was “autosomal dominant familial gynecomastia of an unknown cause” or “aromatase excess syndrome” or “Antley–Bixer syndrome” among others.

(In my research on Olmec babies, it seems like there was a trend for pathologizing historical figures or peoples to fit literal interpretations of art in the 1970s.)

The Fetal Mummies

On the back of all this shallow-gene-pool theorizing the fetal mummies found in his tomb were assumed to have been miscarried/stillborn due to inbreeding if they were even his.

So in 1978, when researchers radiographically examined the larger fetal mummy, 317b, their bias was confirmed by finding multiple congenital anomalies such as Sprengel deformity, spinal dysraphism, and scoliosis. The verdict was that the 18th dynasty had (in)bred itself out of existence, case closed.

Listen as the distant banjo music is carried on the wind through the Valley of the Kings.

In 2001, historian Geoffrey Chamberlain proposed another theory, with nothing to do with inbreeding: the girls could have been twins with twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, to explain the size discrepancies as well as their deaths. Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome occurs only in identical twins who share a placenta. One twin ends up getting more nutrients than the other, and without intervention, the smaller twin may die in utero, which puts the larger twin, and the mother, at risk of miscarriage and death.

Tutankhamun Family Project

In 2008, the fetal mummies were part of the Tutankhamun Family Project, a substudy of the Egyptian Mummy Project. In this study, multiple members of King Tut’s family had their DNA analyzed as well as CT scans performed. Researchers discovered that there were no signs of congenital issues in his family that would result in premature death or infertility (Hawass, et al. 2010). They theorized that by having multiple exogamous (unrelated) wives and having half-siblings marry, the risks of recessive congenital diseases were significantly reduced in their extended family.

They also determined that King Tut was a relatively normal-looking young man for his rank and for his family: he had artificial cranial deformation as a baby to achieve an elongated skull shape/flat head of the royals, as well as that overbite (which isn’t any worse than the actor playing Mike Wheeler in Stranger Things during the first season).

But what about the man boobs? I hear you ask

There is no evidence that any of the 18th Dynasty men had gynecomastia, rather, as Krishna Seshadri explained in 2012, the boobs (and wide hips) seen in art were symbolic:

“Akhenaten switched allegiance from Amun and a pantheon of Gods to a monotheistic form of worship that honored Aten, an androgynous deity who embodied the male and the female. The king usurped the title of the living God and by extension had images of him and his lineage made to the likeness of Aten. The images were symbolic and not realistic depictions.”

Seshadri, Krishna G. May-June 2012. The breasts of Tutankhamun. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 16(3): 429–430.

So no, King Tut didn’t have an adrenal tumor, or Klinefelter’s, Wilson’s, Antley–Bixer’s, or aromatase excess syndrome but he did have a slightly pronated foot (the diagnosis of club foot is up for debate). Due to an injury (or trying to correct his gait), he had developed a kind of bone necrosis in his foot which develops owing to pressure on the bones in childhood, a condition which was very painful, thus he had a variety of walking sticks and was pictured sitting in situations where other pharaohs would be shown standing (but not always).

And I would like to point out that many of the physically obvious conditions ascribed to King Tut over the decades such as clubfoot, scoliosis, cleft palate, a class II malocclusion (overbite) do not require multi-generational inbreeding to occur.

Edit: I want to clarify that I am not making light of inbreeding and the risks for recessive congenital conditions. But I do have a serious problem with medical theories about historical figures or peoples that had, and have, no substantiating evidence.

But if he was healthy, then why did he die so young?

There were other health concerns, such as chronic malaria and schistosomiasis but these were endemic to the region, and members of his own “inbred” family lived to old age with them. King Tut died young, not because of inbreeding but because he lived nearly three-and-a-half thousand years ago and life expectancy was grim even for pharaohs, especially after a compound leg fracture which seems to be the most up-to-date theory for his primary cause of death.

Yes, ancient Egyptians had a relatively advanced medical practice for the time but a broken leg, especially a compound fracture (which means the broken bone is protruding from the skin). This kind of injury could kill the healthiest person without access to antibiotics and possibly a blood transfusion, along with the risks of blood clots and rogue bits of bone marrow, let alone for someone with an underlying disease burden of chronic malaria and schistosomiasis.

Finally: King Tut’s Daughters

Based on DNA, King Tut was the father of the babies found in his tomb, with over 99% certainty and they believe that his wife and half-sister was their mother (the body they believe to be hers had more deteriorated DNA). Despite many theories that he was suffering from a congenital disease that left him infertile, King Tut had fathered at least two children before he was twenty years old. Based on the CT scans, his daughters were 24 weeks and 37 weeks gestation respectively, and both were artificially mummified, including filling out the legs of 317b.

So despite his mother and father being full siblings, King Tut was healthy and fertile enough to produce children. But did fathering them with his half-sister result in their deaths like the 1970s researchers claimed?

Contrary to the radiographic examinations in the 1970s, there were no skeletal abnormalities or causes of death found during the 2008 examinations of the fetal mummies. In 1978, researchers had mistaken post-mortem damage to 317b for those “multiple congenital anomalies”. A classic case of finding what you’re looking for instead of what was really there. As to Chamberlain’s 2001 twin-to-twin transfusion theory, the DNA results ruled out them being identical twins, therefore they couldn’t share a placenta and gestational ageing ruled out them being twins at all.

Like many miscarriages and stillbirths today, these babies would have seemed perfect to their families and due to the Egyptians’ remarkable skills at preservation, they looked perfect to both Carter and Derby nearly 3300 years later. Their loss must have been heartbreaking and inexplicable for their family and, possibly, for the realm. I’ve focused on King Tut but if their marriage was based on love (rather than purely familial/royal duty) the loss of Ankhesenamun’s pregnancies followed by the loss of her husband/brother/king must have been devastating, especially considering that she had already lost her parents and older male siblings.

Why they were Buried with their Father

Historians point out that as Pharoah, King Tut could have had his children interred in their own royal tombs but he chose, or his wife chose, to have his daughters interred with him. I wonder where they were kept between their mummification and his death. As a young man, he likely believed his death to be a distant event and probably expected to father (and perhaps even lose) more children.

Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley suggested that there was a cultural belief that daughters were guardians of their families and by being put to rest with their father, their souls would have accompanied and protected their father’s soul through the underworld on their way to the afterlife. Perhaps as babies who died before birth, they had a special status with Osiris, having never fully joined the world of the living.

Fetal Mummies in Egypt

King Tut’s daughters are not the only example of mummified fetal remains in Egypt: Hawass et al explained that stillborn infants and fetuses were buried with their parents, with examples of a perinatal skeleton found with Queen Mutnodjmet near the tomb of King Horemheb; Ernesto Schiaparelli found one in the Valley of the Queens around 1905, now on display in the tomb of Amonherkhepershelf.

As covered in a previous Rabbit Holes, in the tunnels of Saqqara, possibly millions of small mummy cases are seen, previously believed to be the remains of hawks or other small animals sacrified as prayers. However, when one (EA 493 Mummified Hawk), was examined through CT scanning at Maidstone Museum in Kent (UK), it showed the remains of a stillborn male fetus with what appeared to be neuro tubal defects. The mummy case was decorated with human feet in sandals but with hawk iconography. Bettany Hughes suggested that the artwork symbolized the soul’s flight to the afterlife where the child could be reunited with their family. How many of the tiny mummies in the tunnels of Saqqara contain human remains?

All of this gives a picture of how fetuses and newborns were valued as members of the family and community in ancient Egypt, right across the economic spectrum. They had some level of personhood, though not individual names, as we saw from Tut’s daughters’ coffins which only carried the name of the Orisis, god of the dead. It makes me wonder if attempts were made to revive or provide life support for premature infants.

A Third Tiny Coffin

There is another mini coffin (also nested) resembling the other two, catalogued as item 320, believed to have been turned over by intruders, but with no mention of another mummy.

“N.E. corner of chamber; placed on top of shawabti kiosks, between Nos. 317 and 322; probably turned over and displaced by the intruders.”

“Beside the third coffin (320, B), also wrapped in a piece of linen, a solid gold statuette of the King Amenhetep III, suspended upon a gold chain ending with linen cords having each a tassel. Around the neck of this squatting gold figure, a minute bead necklace, the string of which decayed.”

Howard Carter’s Notes

The lock of plaited hair may have belonged to Queen Tye (Tut’s grandmother) based on inscriptions on the 4th coffin. The little squatting figurine is reminiscent of depictions of Horus (god of the sunrise) and is shown with pharaonic regalia and pierced ears. Pierced ears were popular with women and some young princes but not adult men, for example, Tut’s grandfather was never pictured with them. Though Tut himself and his father Akhenaten were depicted with earrings, they weren’t expected to wear earrings beyond boyhood. This has led to theories that his famous gold death mask wasn’t originally intended for him because of the pierced ears, but earlier the older looking bust found in his tomb shows him with pierced ears too.

So who is the squatting figurine representing? As far as I have found, no one really knows. I would like to learn more about the significance of this third little coffin and its contents. Was it a memorial to another miscarriage? Too early in the pregnancy to preserve the body? If it was a memorial for another miscarriage, was it set apart from 317 because they believed it to be a male baby? (early in pregnancy, fetal genitals are ambiguous). And why include the lock of possibly great-grandmother’s hair? Was it to help the spirit of the child find their family in the afterlife? Or to call upon Grandma’s assistance in the afterlife? Some researchers have suggested that in an effort to distance himself from his heretical parents but still honour the memory of his pharaonic ancestors, he focused on his grandparents. Whatever the case, the pendant is now at the Egyptian Museum in Cario.

Closing Thoughts

As usual, I started this project with the aim of making a “short” and ended up researching the topic for months. I was surprised to learn that King tut had children and that the theories about his poor health and strange looks were largely unfounded.

It reminds me of the depictions of King Edward VI (Henry VIII’s son and successor) being a sickly weak child and therefore dying young without heirs. But it’s not true, he was healthy, as a young child he survived acute malaria and in the last year of his life he survived a double whammy of smallpox and measles, and was on the road to a full recovery when TB took advantage of his weakened immune system. These were endemic, deadly illnesses, one need not be congenitally weak or sickly to die of malaria, smallpox, measles, or TB. (Over a million people died from TB in 2021 despite humanity having a cure for it.)

Maybe we come up with these stories to make sense of young men dying prematurely because we expect rich and politically powerful males to be impervious. But when they aren’t, they must have always had sickly and weak constitutions. Hindsight isn’t always 20/20.

This also brought to mind modern initiatives to support grieving families following miscarriage and stillbirth. For example, providing parents with a space and time to see their baby, to say their hellos and goodbyes, and to have photos taken and keepsakes created. In this way, ancient Egypt may have been more conscientious than many modern cultures in recognizing the grief of miscarriage and stillbirth.

Sources

Burzacott, Jeff. 31 Aug 2015. “Is this a precious memento of the grandfather than Tutankhamun never knew?” Nile Magazine.

Graslie, Emily. 20 Oct 2016. “Why did King Tut have a flat head?” Field Museum. [article and video]

Hall, Tamron. 22 April 2010. “King Tut.” NBC: Today Show.

Hawass, Zahi and Yehia Z Gad, Somaia Ismail, et al. 2010. “Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family.” JAMA 303(7), 638-647.

Lovegren, Stefan. 1 Dec 2006. “King Tut Died From Broken Leg, Not Murder, Scientists Conclude.” National Geographic.

Seshadri, Krishna G. May-June 2012. The breasts of Tutankhamun. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 16(3): 429–430.

Wilkins, Alasdair. 30 Nov 2011. “Why inbreeding isn’t really as bad as you think.” Gizmodo.

http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gri/carter/ [Carter’s photographs and notes]