Natural birth

Today the phrase “natural birth” in the West can bring to mind anything from a conventional hospital birth just without anesthetic to a planned unassisted birth without any medical assistance at all. Though wildly different in scope, the general idea is that a modern natural birth is a conscious choice by the pregnant person to reduce or eliminate medical interventions during labor and birth. But natural birth in the Tudor era had a very different definition, a natural birth was the opposite of an unnatural birth. The 1540 book The Byrth of Mankind explained:

“But ye shall note that there is two manner of births one called natural the other contrary to nature. Natural birth is when the child is born both in due season and also in due fashion. The due season is most commonly after the ninth month or about 40 weeks after the conception […] The due fashion of birth is this […], first the head cometh forward then followeth the neck and shoulders the arms with the hands lying close to the body toward the feet. the face and forepart of the child being towards the face and forepart of the mother as it appears in the first of the birth figures”

A natural birth is one that is term (around 40 weeks gestation, the due season) and one in which the baby presents in Occiput Anterior or OA positioning, it is the most common presentation and even today is considered to have the lowest risks associated with it.

It was also believed that a natural birth should be relatively easy,

“another thing also is this that if the birth be natural the deliverance is easy without long taryenge or lokynge for it.”

but unlike today, the majority of people in the 16th century would have had personal experience losing siblings, mothers, aunts, female friends in childbirth, or of losing their own babies. In the Tudor era, instead of birth plans, women wrote their wills during pregnancy.

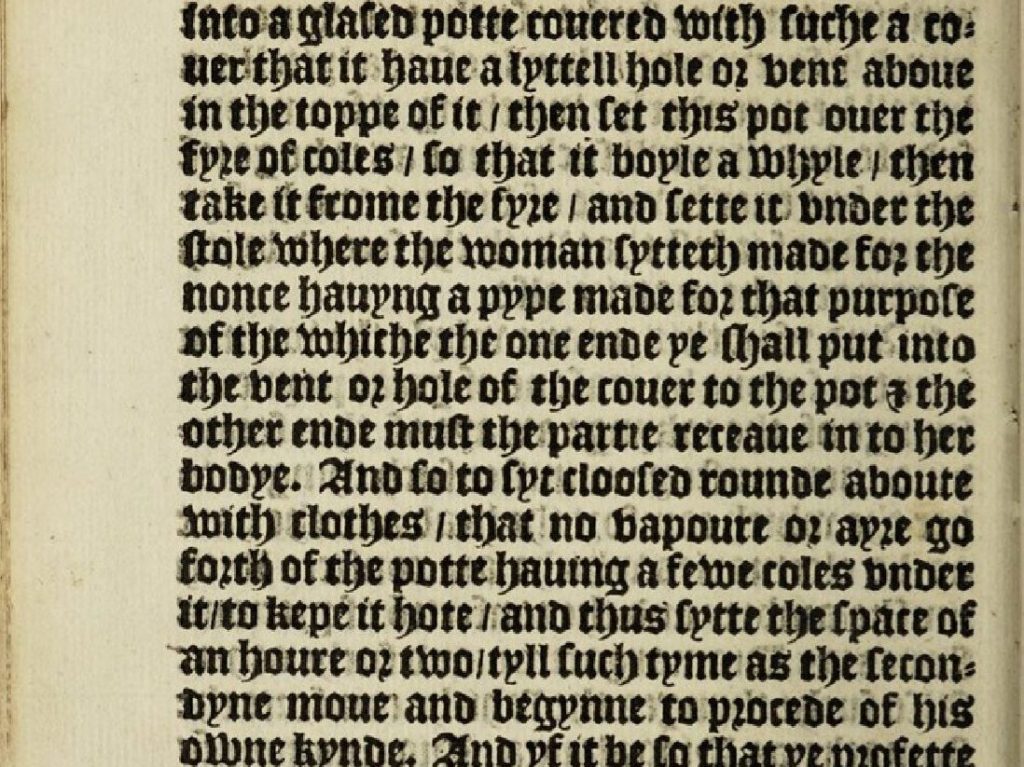

In the 16th century in Europe, labor and childbirth were women-only affairs, off-limits to men, save in very limited situations. Women didn’t really write or talk about the experience of being pregnant or giving birth, it wasn’t a matter for public discourse save for those of a celebrity, like the Queen. So when The Byrth of Mankind was first published in English, in 1540, it was considered groundbreaking (even though the information and concepts inside were over a thousand years old).

For that reason, and the fact that it was authored (translated and expanded) by a man, it is hard to know what elements of the recommended practices in that book would have been new to the women and midwives it was marketed at–maybe they had already been doing all the things it recommended; it’s unlikely that the contemporary male authors/translators would know one way or the other.

In her essay on Birth Figures, historian Rebecca Whiteley explained that at the time Nature was personified and believed to be an active agent in the body. It was thought to actively work towards a state of humoral balance in the body. The early modern healthcare provider believed that health was the natural state and they only needed to find ways to support it in an unnatural world. (Today this is recognized as fallacious reasoning known as “appeal to nature”. )

Therefore, it would seem obvious that childbirth, if entirely natural, should be relatively easy on the woman. It’s a hopeful idea, especially for the male writers of childbirth manuals. Literate mothers and midwives would have been eager to find signs that an impending birth would be a natural one.

According to The Byrth of Mankind they include:

Qualifications

- Expectant mother over 15 years old

- Not too old (whatever that means)

- Not fearful

- Obedient

- Strong and mighty of nature

- Moderate weight (not under or overweight)

- Pregnant with a male child

“also you must understand that generally the birth of the man is easier than the birth of the female”

Signs

- Active fetus, lots of kicking and moving

- Previous natural birth

- Labor pains come in the lower part of the belly

“These signs betoken and signify good speed and luck in the labor: unquietness, much steering of the child in the mother’s belly, all the throngs and pains tumbling in the fore part of the bottom of the belly, and when the woman is strong and mighty of nature and such as call well and strongly help her self to the expelling of the birth.”

p40

Women and their unborn babies were considered to be active agents in the birthing process, both needed to be strong and active. If either one wasn’t able or willing to do their part birth would become drawn out and even dangerous– making it unnatural.

With that in mind, there were some things that a woman and midwives could do (i.e. interventions) to help ensure that if they were favored by Nature with a natural birth, that it would remain natural:

Things you can do to Prepare:

Diet and Exercise

“She must take good heed to her diet that she take things the which may comfort and strengthen the body. Feeding not over much of anything and to drink pleasant and well-savoring wine or other drink. Also moderately to exercise the body in doing something, steering, moving, going, or standing more than otherwise she was wont to do: these things farther the birth and make it the easier, and this is the manner of diet the which we advise the woman to keep the month before her labor or longer.”

The pregnant woman is advised to avoid constipation by eating foods that have a laxative effect, along with the use of a “clyster” or enema of broth or a suppository of soap/lard/egg yolk if needed to get things moving. Why?

It’s because they saw pooing as being sympathetic to childbirth: if poo isn’t coming out easily, then baby won’t either. When labor (or the menstrual period) begins many women develop diarrhea due to the prostaglandins stimulating the smooth muscles of both uterus and bowels. This is the source for the old-wives tales for bringing on labor with laxatives like castor oil. Even though some stimulant laxatives may cause uterine contractions along with intestinal contractions, it’s not a means of jumpstarting labor.

There is a separate diet recommended once labor has begun:

“Another diet there is the which she ought to observe in the time of labor, when the storms and throngs begin to come on, and the humors which yet hitherto have remained about the matrice or mother collected now begin to flow forth: and this manner of diet consisteth of two sorts. First that such things be procured and had in readiness which may cause the birth or labor to be very easy. Secondly to withstand, defend, and to put away so near as may be the instant and present dolors. And as touching this point, it shall be very profitable for her for the space of an hour to sit still, then rising again to go up and down a pair of stairs crying or reaching so loud as she can so to steer herself.”

During labor it was advised to have on hand food and drink that will help with the birth as well as comfort the laboring woman or reduce her labor pain– with a side of stair climbing and vocalizations.

Medical interventions

And there were various medicinal preparations that could help augment birth, including potions, pessaries, vaginal incense, herbal baths, and various lubricants.

Potions

“Saffron and Syler Montanum provoketh the birth of any living thing if it be drunk: how be it to the woman give never passing a dram at once of saffron for greater quantity should greatly hurt.”

Now, I’m no herbalist but I know that saffron is advised against consuming during pregnancy because it causes uterine contractions, and WebMD (aka you-have-cancer.com) warns that 5 grams causes poisoning and 12-20 grams can cause death. And 1 dram is around 1.75 grams.

While we are on the subject of risks: none of this constitutes a medical recommendation. Do not attempt anything recommended in this almost-500 year old book without consulting with your medical provider, preferably a licensed professional medical doctor.

Pessaries

Pessaries are pills or other preparations, sometimes wrapped in wool, which are put inside the vagina.

“Also it is very good to dip wool in the juice of rue and the same to convey into the secrets. Also the powder of Aristolochia rotunda, or the root called bother martis, or malum terre, or the seed of staphisagre: any of these wrapped in wool and conveyed inward provoketh and calleth forth the birth.”

Vaginal Incense

“It shall also very profitable for her to perfume the nether places with musk, amber, Gallia muscata which put on embers yield a goodly favor by the which the nether places open themselves and draw downward.”

Ever hear the phrase, blowing smoke up your ahh-butt? Well, it’s a thing and in the case of 16th-century midwifery it might get blown up the butt however, they were aiming for the vagina. This concept is based on the principle of attraction combined with the theory of the wandering uterus: people are attracted to good smells and are repelled by bad smells — so organs and fetuses must be too! It makes a case for vaginal incense or fumigation during childbirth (for people who know nothing about the physiology of childbirth). Just make sure that only the vagina gets the good smells or childbirth could get really interesting in an involuntary-rhinoplasty-body-horror kinda of way:

“perfumes put on the embers must be so closely received underneath that no part of the smell do ascend to the nose of the woman. For to the nose should the saver of nothing come but only of such things the which stink or have abominable smell”

Some of the ingredients of these perfumes or incense include bird poo,

“The fume of culver dung or of hawks dung by putting to of oppoponacum is sovereign for the same. All these fumes open the pores beneath and causeth nature to be the freer in deliverance.”

Culver is a bird like a pigeon. A fan of waffle fries.

Some may argue that while this doesn’t work the way they thought it did, it doesn’t hurt and it may make laboring women feel more comfortable. But it’s not harmless, then and now (ala GOOP’s vaginal steaming), there is a risk for burns and adverse reactions to ingredients added to the steam/incense which then increase risk for infections as the tissues heal.

Herbal Baths

How about something more relatable? Like a warm herbal bath:

“But about 10 days before the time (If she feel any pain or grief) let her use every day to wash or bathe her with warm water in the which also that she terry not overlong in the bathing for weakening of her. In the bath let her stand so that the water come above the navel a little, and let be sod in the water mallows, Holyoak, chamomile, mercury, maidenhair, linseed, fenugreek seed, and such other things which have virtue to mollify and supple.”

Edit: I originally wondered about what kind of mercury was being recommended. Mercury (metal) baths were used for medicinal purposes in history, however, a commenter on my YouTube channel who studied herbology noted that there is a flower called mercury and given the context, it seems more likely that they are referring to the flower, not the metal.

Lube Up!

“and when ye are thus bathed or washed then shall it be very convenient for you to anoint with the foresaid greases and oils your back belly navel sides and such places as are near to the privy parts. furthermore it shall be greatly profitable for her to convey inward into the privy parts these four said oils or greases with a sponge or other thing made for the purpose”

The recommended lubricants are hen’s grease, duck grease, goose grease, olive oil, linseed oil, fenugreek oil, holly oak oil, the oil of white lilies, and wine! (lots of wine) And there were medicinal preparations that could be made with the lubricants:

“Anointing the privities with oil or other such greases as I spoke of before in this fashion: Take the oil of white lilies or ducks grease and with that temper two grains weight of saffron and one grain of musk and with that ointment anoint the secret parts.”

Positioning

The Byrth of Mankind introduces the concept of a birth stool, a new-fangled device used by midwives in France and Germany. Once the waters have broken, Jonas writes:

“then shall it be mete for her to sit down leaning backward in manner upright. For the which purpose in some regions (as in France and Germany) the midwives have stools for the purpose which being but low and not high from the ground is made so compase wise, and cave or hollow in the mids that that may be received from underneath which is looked for: and the back of the stool leaning backward receiveth the back of the woman the fashion of the which stool is set in the beginning of the birth figures hereafter.”

But the most commonly recommended position is groveling, between kneeling and all-fours.

“But and if the woman be any thing grosse, fat, or fleshly it shall be best for her to lye grovelying for by that means the matrice is thrust and depressed downard.”

“all such things as help birth and make it more easy are those first the woman that labor is must other sit graveling or else upright leaning backward according as it shall seem commodious and necessary to the party or as she is accustomed.”

Hold Your Breath:

Women were also advised to hold in their breath, [sarcasm font] because that doesn’t make pain worse, like, ever. But hey, if you’re holding your breath, at least you’re being quiet, eh?

“Also it shall be very good for a time to retain and keep in her breath for because that thorow that means, the guts and entrails be thrust together and depressed downward.”

“and in this case also let the woman withhold her breath inward and so much as she can for that she’ll drive downward such things as being the body to be expelled.”

Holding the breath was thought to increase intra-abdominal pressure on the birth.

“bidding her to hold in her breath in so much as she may, also streaking gently with her hands her belly above the navel for that helpeth to depress the birth downward”

Holding breath and applying external pressure to the fundus was thought to speed delivery.

The Midwife’s Role:

The midwife was to above all, provide comfort to the laboring woman:

“also the midwife must instruct and comfort the party not only refreshing her with good meat and drink but also with sweet words giving her good hope of a speed full deliverance encouraging and enstomacking her to patience and tolerance”

“And let the midwife always be very diligent providing and seeing what shall be necessary for the woman.”

And, of course, patience:

“The midwife herself shall sit before the laboring woman and shall diligently observe and wait”

“the midwife about all things take heed of that she compel not the woman to labor before the birth come forward and show itself. For before that time all labor is in vain”

Perhaps recognizing the futility of cervical checks, because the cervix can stay in one place for days or suddenly dilate in minutes, midwives are instead instructed to look for “the birth” as a sign of progress: either a bulging bag of waters or a head or some bit of fetal anatomy.

“When the secondine or second birth (in the which the birth is wrapped and contained) doth once appear, then may ye know that the labor is at hand.”

But it was important that the midwife not be shy about getting in there, you know? Like wrist deep:

“And if necessity require it, let not the midwife be afraid nor ashamed to handle the place and to relax and loose the straits, for so much as shall lie in her, for that shall help well to the more expedite and quick labor.”

In later childbirth manuals, physicians and man-midwives, like Percival Willughby, criticized midwives for being too forceful, causing fistulas or even lifting a labouring woman off her feet by her perineum long before “the birth” was at hand.

Conclusion:

Natural birth in the 16th century was defined as an easy, quick labor after 40 weeks of gestation, the “due season”, to a (preferably male) baby who presents in the OA or “due fashion” position. Unlike modern ideas of “natural birth” which eschew medical interventions, in the Tudor era, medical interventions could be used to augment the birth or to provide comfort to the woman.

A question that keeps occurring to me: is it wise to go into birth believing that it ought to be this easy, quick experience unless something is wrong (or unnatural) with it? Did religious ideas play a role here? For example, in the 16th-century mind, the Garden of Eden may be the only truly natural place which humans were cast out of due to original sin. Furthermore, Eve’s punishment from god extended to all women which was to give birth in pain, so was it a sign of particular grace to have an easy birth or was it a sign of evil?

Some of the recommendations are laughable today, and many are dangerous, but these are just the ones for the natural easy births– wait until we cover unnatural births (which could take a minute because it’s just so horrific).

But are there any 16th-century recommendations that you would consider trying or have tried? Or if you are a midwife, are there any you’d recommend?

If you would like to support my research please consider becoming a patron on Patreon.

Here’s a link to The Birth of Mankind, 1540 at the Wellcome Collection so you can read it yourself.