This amazing painting by Jan van Eyck (1390-1441) features Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini (c1400 – after 1452) (possibly a cousin of Jan van Eyck) and his wife Costanza Trenta Arnolfini (c1413-c1432-3).1 They were both from Lucca (to the northwest of Florence in Italy). He was a prominent Italian merchant. Her aunt was married to Lorenzo de’Medici.

However, Giovanni lived in Bruges (in Belgium) since 1419, networking amongst the Burgundian court. Costanza was betrothed to him at age thirteen, on January 23, 1426, and resided with in him Bruges after their marriage. Tragically, Costanza died before February of 1433, probably around 20-21 years old. On February 26, 1433, her mother, Bartolomea, wrote to her sister, Lorenzo de’Medici,

“solamenta ne viveno due, Paulo e Johi. Mor[t]o la Costanza e Lionardo. Paulo si trova in Avignone… Johani e a lucha..”

“Only two are alive, Paulo and Johi. Costanza and Lionardo are dead. Paulo is in Avignon… Johani [in] Lucha.

Florence Archivio di Stato, Mediceo avanti il principato,xx/40; letter dated Lucca 26 February 1432/33.

The painting, however, is signed 1434. If its a wedding portrait, as many have argued, why did it take so long to complete? And why does she look pregnant?

Symbolism

Medieval and renaissance art is full of symbolism, think of them like the “easter eggs” you may find in your favorite movie, show, or video game hinting at deeper knowledge or meanings. These symbols allow informed and curious viewers of the art to “read” the piece. But miscommunication is rife, especially across the centuries and it’s changes in culture, language, fashion, and art itself. We’re used to photography, so it can make sense to say, “well this painting couldn’t have been of Costanza then, because she was already dead”– or in the case of the Cholmondeley Sisters portrait, presuming that both babies must have been born at the same time to look the same age in the painting. But we forget (and are soon to remember thanks to AI art) about artistic license. If Jan van Eyck had seen the lady prior to her death, or even at her wedding, he could paint her whenever from memory. So sure, this could be their wedding portrait but that’s not was the symbology is telling us.

There have been centuries for people to decide what this portrait was about and for, and for at least the last century or so, thanks to Erwin Panofsky who published his theory in 1934, the consensus was a wedding portrait.2 But at the dawn of the 21st century, Margaret L Koster discovered Bartolomea’s letters in the Florence archives, reading the sad news of her children’s deaths. Suddenly, the idiosyncratic symbology of the painting revealed itself, in 2003 she published, “The Arnolofini Portrait: a simple solution.”

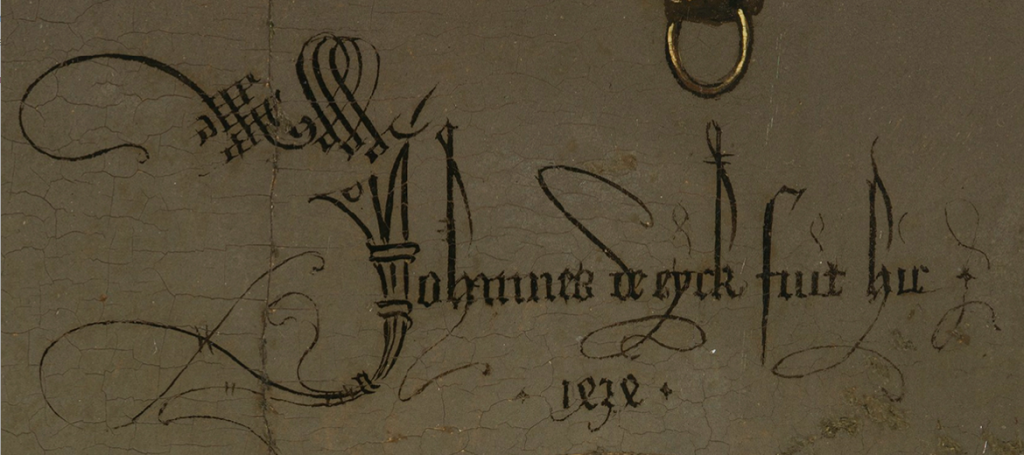

Koster argued that the painting may have started as a portrait of a newly wed couple but then changes were made when it became a posthumous (after her death) portrait of her as well as a symbol of Giovanni’s grief and devotion. Along with Jan van Eyck’s writing on the wall, “Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434” (Jan van Eyck was here 1434), and their reflections in the mirror, it is at once a celebration of life and a momento mori, or a reminder of death. They were all once alive and now they are gone, like a reflection in a mirror, so too shall we be.

Maternity

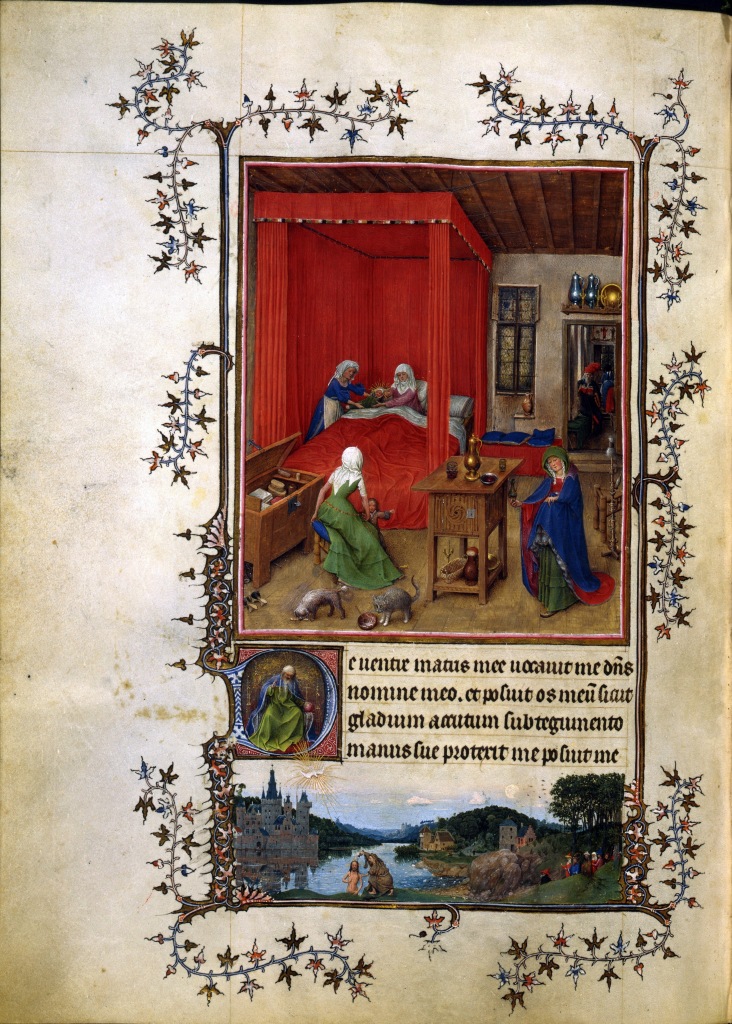

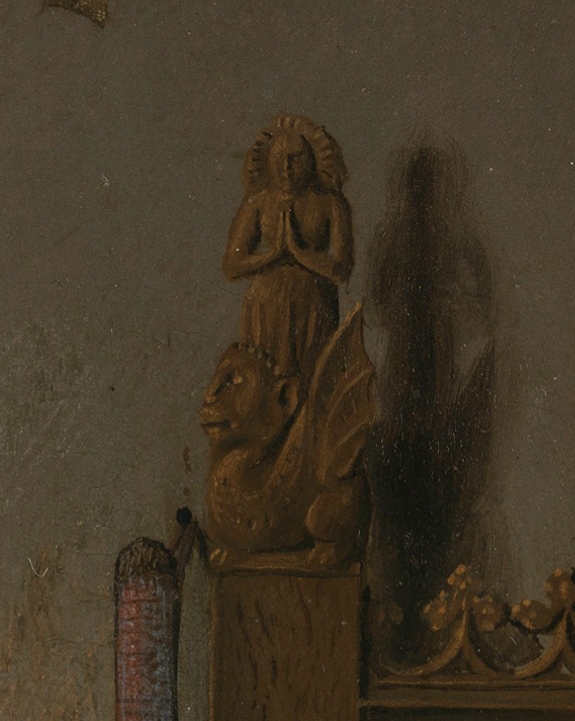

There are a number of elements in the painting to suggest she wasn’t just a beautiful young wife but that she was also pregnant. First, most people notice the dress and her posture and assuming pregnancy– but that was the fashion, even for virginal saints, like Jan van Eyck’s portrait of St Catherine (below) (and never forget the Belly Pad Craze of 1793). However, just because virgins (the non-immaculately impregnated kind) dressed to emphasize their bellies, doesn’t mean we should discount her being pregnant. There’s plenty of symbolism to support that she was pregnant: there is a “hung bed” which is often used in paintings of this era to show a lying-in chamber or a death scene (sometimes one and the same). There is a chair in the background featuring a carving of the patron saint of pregnant women, St Margaret, not seen in the underpainting. The carpet too, just one mind, as recommended by Alienor de Poitiers 15th century guide3 which explained that noble women may have one carpet, placed in front of her bed while giving birth, while the highest ranks may carpet the whole floor.

They are dressed formally, far more formally than they would be in a domestic setting, however, both of them have removed their shoes. Removal of shoes was an expectation of being in a sacred space, or in art, to denote sexual passion. My guess is that its symbolizing both, in the sense that married sex was considered sacred (though not a sacrament in Catholicism) and for the procreation of children. Behind them there is fruit on the window sill and a cherry tree outside the window, the message is clear: they are fruitful.

We see Giovanni raising his right hand, this gesture is associated with the Latin fides, or fidelity, that is, keeping an oath or promise. Augustine’s fides, is one of the three goods of Christian marriage.4 Giovanni may be referencing an oath already made, he remains faithful to his marriage vows. Art historian Waldemar Januszczak believes it symbolized the annunciation, in other words, a pregnancy announcement. Investigations of the under painting show there were changes to the position of the hand, so perhaps it’s a bit of both.

Mortality

Down by her feet, there is a little dog, seen on the tombs of ladies, such as Margaret of Austria’s. They were an emblem of marital faith and mutual affection between spouses. In the under painting there was no dog featured, a hint that this painting probably wasn’t planned as a posthumous portrait but she died while it was being painted.

On the wall, that famous mirror, with scenes of Christ’s life, death, and resurrection around it. The scenes of life are on Giovanni’s side and the death and resurrection on Costanza’s side. The under painting showed a larger octagonal mirror, with no biblical scenes.

Look up at the chandelier, on Giovanni’s side, a candle still burns on his side. On Costanza’s side, there’s just a bit of wax left for us to know a candle was ever there. This chandelier, like the dog, wasn’t in the original underpainting.

The colors and the lighting in the painting also have symbolic meaning. She is bathed in a otherworldly glow, swathed in brilliant colors associated with love: green and blue with white fur linings. Sharply contrasted by his garb, he seems to be mourning in the shadows wearing dark purples and black (before darker colors became popular).

On the wooden bench, we see a carved grimacing monster, just above their joined hands, seeming to threaten their union. The under painting shows Giovanni having a better grip on Costanza’s hand but in the final painting, her hand seems to slip from his.

I am grateful for Giovanni’s love and devotion to his wife, and for Jan van Eyck’s incredible skill. Yet it is a very sad story. Giovanni lost not only his wife, someone from his hometown who shared his culture and language, but also his child. If this portrait wasn’t planned as a posthumous portrait (due to the changes to the mirrors, and the addition of the chair, dog, and chandelier) it’s possible we would still have a richly detailed portrait of this couple even if she had survived the pregnancy and childbirth.

As far as Koster could find, Giovanni never remarried. All of them live on in our memories for the (possibly billions) of people who have seen this painting and learned about them, which now includes you if you’ve read this far. (Thanks!)

Sources

Billinge, Rachel and Lorne Campbell. 1995. “The Infra-red Reflectograms of Jan van Eyck’s Portrait of Giovanni(?) Arnolfini and his Wife Giovanna Cenami(?).” National Gallery Technical Bulletin, Vol 16, pp 47–60.

Januszczak, Waldemar. 28 June 2022. “The Arnolfini Marriage by Jan van Eyck.” In The Art Mysteries, s2e4. BBC. Watch on YouTube.

Koster, Margaret L. Sept 2003. “The Arnolfini Double Portrait: A Simple Solution,” Apollo, 158(499): 3-14. (see file below)

Leininger-Miller, Theresa. (nd). “Renaissance Masterpiece:

Jan Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434).” University of Cincinnati, College of DAAP.

Foot Notes

- There were two Arnolfini’s living in Bruges at the time, the one in our portrait was older and had lived in Bruges longer. The younger Arnolfini married Jeanne de Cename (or Cenami) in 1447, but our Arnolfini was betrothed in 1426 and never remarried. For a long time there was confusion about who exactly was in the painting but while an artist can paint anything in the present or the past, painting the future is beyond the scope of even Jan van Eyck. ↩︎

- Check out Dr Theresa Leininger-Miller’s pdf presentation, linked above. ↩︎

- (a bit after Costanza’s time) Les Honneurs de la Cour, 1484-91, by Alienor de Poitiers, widowed Viscountess of Veurne. “… a noblewoman below the rank of countess normally placed only one carpet in front of her bed when she was giving birth; only a lady of the highest rank was permitted to carpet the entire floor of her lying in chamber.” ↩︎

- Coughlin, John J. 1 May 2007. “The Goods of Marriage in Canon Law.” Notre Dame Legal Studies Paper No. 07-28 ↩︎